“Pay-for-Success bonds” — also known as social impact bonds (SIBs) — are an innovative public finance mechanism that have attracted a lot of interest in recent years. They were first introduced in Western Europe. The idea is to leverage private sector capital and ingenuity to generate positive impacts for underfunded social problems.

While there are few rock solid SIB success stories to point to, several governments have moved to pilot their own SIB programs. Many of them revolve around criminal justice, including a program being proposed in Washington this legislative session by state Representative Hans Zeiger (R-25th).

HB 1501

The very first SIB was implemented by UK policymakers in 2010. The program aims to apply private financing to reduce recidivism by 7.5% among former inmates of the HM Prison in Peterborough. Some U.S. states have followed suit. In 2012, New York City introduced the first American SIB, while a second, in Massachusetts, worth $18 million, launched this January. Both of these programs target prison recidivism as well.

The proposal in front of Washington legislators is very specific. It “authorizes the Office of Financial Management to procure and enter into a multi-year pay-for-success contract with an investor and a provider that requires the investor to finance a social service intervention for 16-20 year old youths exiting a juvenile rehabilitation institution who are at risk of re-entering a criminal justice system or homelessness.”

As Representative Zeiger put it: “The idea is that we need to get the private sector involved in social problems.”

Last year, Representative Zeiger sponsored a similar bill which after sailing through House Early Learning & Social Services Committee, died in the House Appropriations Committee.

If this year’s bill, HB 1501, passes, Washington will join a handful of states who are testing out Pay-for-Success models as a way to combat social problems in an era of constrained revenues.

What does “Pay-for-Success” Really Mean?

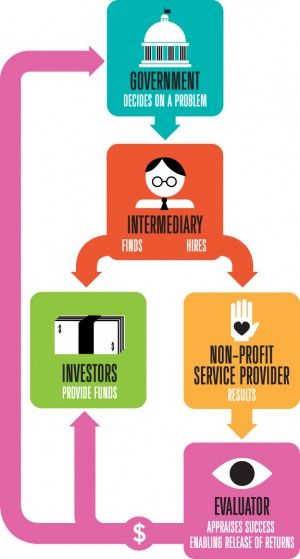

SIBs work like this: funding is obtained from private investors to pay for social services. If these interventions result in better outcomes, the result is savings for government and a return for investors.

SIBs are truly unique in their emphasis on performance. The private investors financing the will not be paid back if the program being funded doesn’t measurably improve outcomes.

SIBs are truly unique in their emphasis on performance. The private investors financing the will not be paid back if the program being funded doesn’t measurably improve outcomes.

Because service providers are paid in advance under a SIB, this form of PBR removes the upfront costs of service delivery from government and shifts the financial risk to private investors.

Why Criminal Justice?

- A surprising number of SIB programs revolve around reducing recidivism, which is defined as the percentage of formerly incarcerated person that return to prison within 3 years of their release. So why has reducing recidivism become such a popular choice for SIB programs?

- Recidivism is easy to track. The state department of corrections logs this information in a database, searchable by name or DOC (department of corrections) number.

- Tracking recidivism produces binary data (the individual either recidivated, or they didn’t). This type of data is much easier to analyze compared to outcomes that occur on a scale.

- There is mounting research about how to reduce recidivism. The number of incarcerated people has ballooned since 1980, and public frustration about the high cost and ineffectiveness of incarceration is growing. Thus, more brain power has been directed towards how we can prevent reoffending.

- The public is increasingly aware of the connections between incarceration and issues like poverty, addiction, and employment prospects after a stint in prison.

- Potential savings are huge. Washington taxpayers spent nearly 6 million dollars on corrections in 2013, amounting to an average cost of $89 per inmate per day.

Although we won’t have final results until 2016 regarding the success of the Peterborough program, things are looking good so far. The UK’s Ministry of Justice released a report in 2014 detailing the interim results of the program.

Although we won’t have final results until 2016 regarding the success of the Peterborough program, things are looking good so far. The UK’s Ministry of Justice released a report in 2014 detailing the interim results of the program.

So far, the program has reduced reoffending by 8.4 percent when compared to a control group.

If the reduction in reoffending remains above 7.5 percent, the Ministry of Justice will make payments to investors.

A reduction of 10 percent was needed to trigger immediate repayment to investors, but the Ministry of Justice maintains that investors are on track to receive positive returns (payment with interest) in 2016.

Juvenile Justice and Recidivism in WA

Washington has a recidivism rate of 28.7%, meaning that almost 1 out of every 3 adults exiting Washington prisons will return within the next 3 years.

A study released in 2014 by the Bureau of Justice Statistics found that theprobability of recidivism decreases with time. Their data revealed that 43% of those who recidivated were arrest within the first year of their release. Evidence like this suggests that the situation is ripe for early interventions that can yield big results.

The recidivism rate for adults may seem irrelevant to the SIB program being proposed in Washington, which focuses on juvenile justice, but there are strong connections between youth incarceration and adult incarceration. Many offenders first come into contact with the criminal justice system as juveniles, initiating a life-long cycle of repeated incarceration.

What Washington Needs to Get Right

The success of the SIB depends on choosing an effective program. There aren’t many programs that carry evidence of a quantifiable improvement in outcomes. Identifying one that can be measured is the first step.

Harvard’s Social Impact Bond Technical Assistance Lab (SIB Lab) provided technical assistance to several state and local governments looking to realize social change through SIBs. The group commented on the challenges of selecting programs with proven success. In their report, they said they expected the “first applications of the SIB model to involve replication and scaling of proven interventions. However, experience has shown that rigorously proven models do not exist for most of the preventive investments that are the highest priorities for state and local governments.”

If there isn’t an array of vetted programs to choose from, states have the option of reviewing evidence from similar programs. However, the policy areas where proven interventions exist do not always overlap with the local provider’s capacity to scale up or with an area in the budget that needs cutting.

If Washington’s program is to be successful, the chosen intervention needs to have ample evidence supporting its effectiveness. Luckily, as mentioned above, there is plenty of research that can be used to inform the state’s decision.

If Washington’s program is to be successful, the chosen intervention needs to have ample evidence supporting its effectiveness. Luckily, as mentioned above, there is plenty of research that can be used to inform the state’s decision.

A New Perspective

The popularity of SIBs represents a shift in how we approach human services. The SIB movement has revealed the dearth of evidence regarding the effectiveness of social programs. If anything, SIBs will generate data about programs that work and the ones that don’t.

Although the popularity of SIBs was born out of an austere budget climate, the attention has ignited interest in measuring the effectiveness of social services. Perhaps, the new emphasis on quantifiable impact is something that both parties can get onboard with.