It’s no secret that Washington’s infrastructure is crumbling. There are many roads and highways throughout the state that need repair, but the state’s unincorporated areas face a significant disadvantage when seeking funds for desperately needed road repairs.

This session, state legislators are finally poised to pass a transportation package, but both the Senate and the House have yet to take up the issue of funding for roads in unincorporated areas. If unaddressed, it will force many counties to lower speed limits significantly, allow roads to go to gravel, and shut down some roads entirely.

How did we get here?

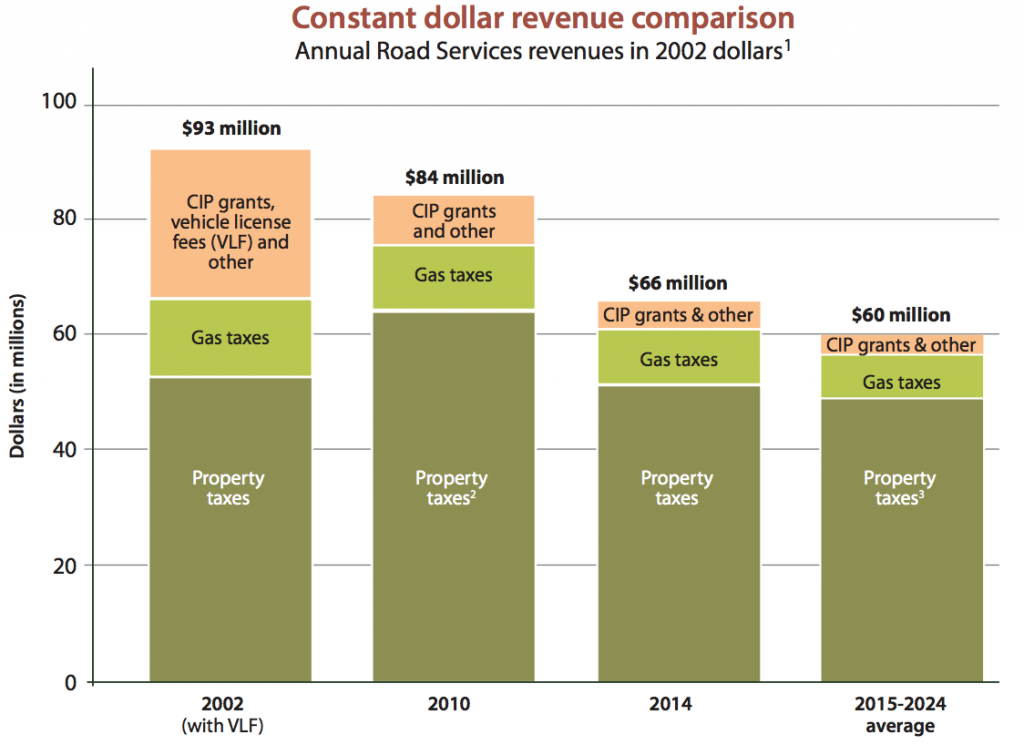

Recent economic history hasn’t helped state revenues. During the recession, property values fell almost 40 percent. They’ve since risen, but property taxes have not rebounded because state law only allows them to rise 1% a year. At that rate, it’ll take the county at least 40 years to shake off the recession’s grip.

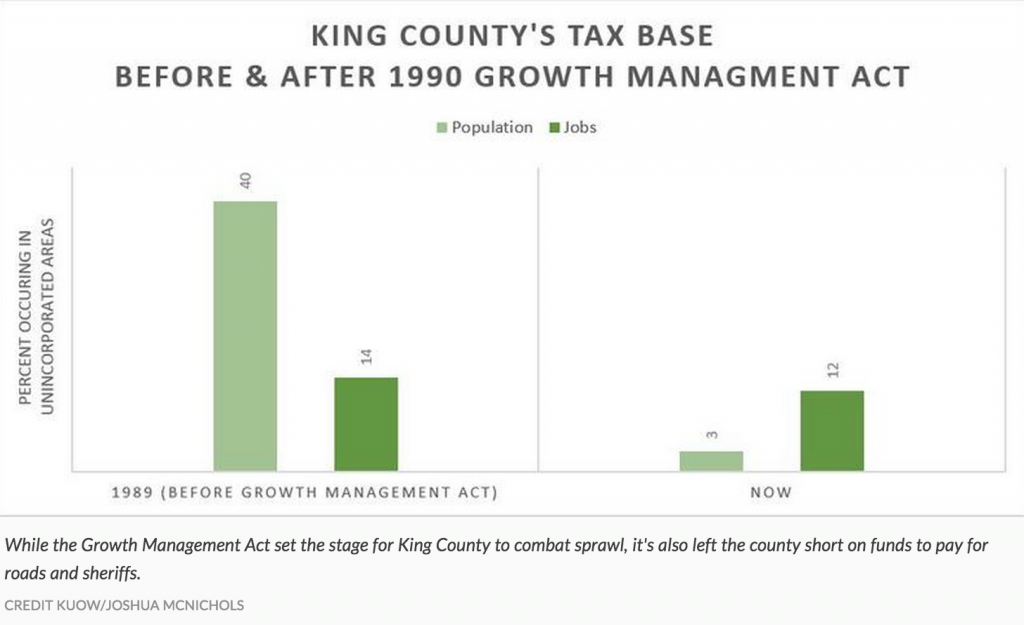

But the makings of this situation extend well beyond the Great Recession. The current crisis is partly an unintended consequences of Washington’s focus on combating urban sprawl. The state’s Growth Management Act of 1990 empowered cities to annex unincorporated areas. That left fewer people in the county to pay for a relatively costly road infrastructure. During annexations King County retained 73%of the roads and 0% of the tax base. To make matters worse, low-density infrastructure is especially costly on a per resident basis.

Case in Point: King County

Kathy Lambert represents northeast King County, which makes up a large portion of unincorporated King County. The County’s unincorporated areas contain 1,500 miles of roads and 180 bridges which carry more than 1 million trips per day. At present, these roads are maintained by Road Services Division.

The over 1,500 miles of roadway that Road Services is responsible for has been ranked into one of five tiers. Tier 1 roads will receive the most service, while Tier 5 roads will receive the least. Tier 1 roads carry 50% of traffic in these areas.

The Roads Services Division is supported by local property and gas taxes, as well as some grant funding. Average assessed residence values in unincorporated King County fell by almost 40 percent from 2010 to 2013, and future growth in revenues is limited by state law.

Estimates show that it would cost $350 million annually over 10 years to fully address the current backlog of needs and bring the system into a state of good repair. Forecasts say the county will generate $90 million annually under the current revenue structure – a structural funding gap of $260 million a year.

Councilwoman Lambert saw the opportunity to solve this problem for her district, as well as many other counties that face the exact same problem. She’s pushing state legislators to add money to the state transportation package for county roads. She also wants legislators to approve a countywide transportation benefit district, so it could raise funds through other avenues, such as a car tab increase. That would allow cities to share the cost of maintaining county roads.

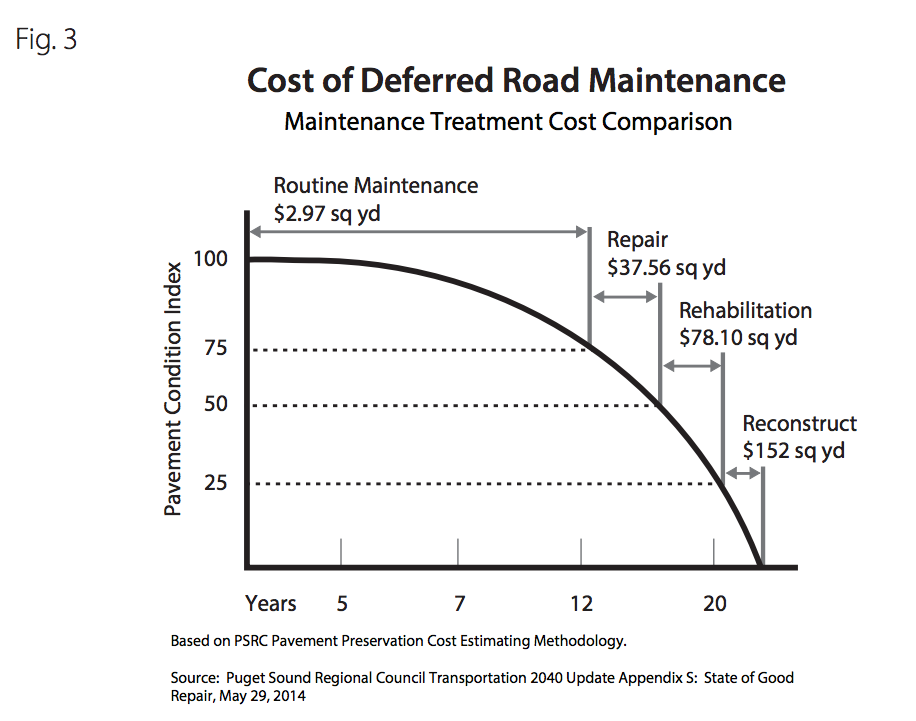

Lambert is also working to establish criteria using the statewide ratings of the County Road Administration Board (as opposed to the tier system used by the Roads Services Division) to triage road maintenance in a way that prevents repairs from becoming so costly that they become unfeasible within the state’s budget. Using the curve below, Lambert’s plan focuses on repairs for roads with a Pavement Condition Index of 75-100, avoiding the huge jump in repair costs that comes once a road drops below a score of 75.

Mounting Crisis

It’s no exaggeration to call this situation a “crisis.” The matter is time sensitive and the consequences of inaction will be severe. If the emerging 16-year transportation package restricts local jurisdictions from bonding for further road repair funds, there won’t be any mechanisms to fill these gaps. Preventive maintenance is a bargain compared to reactive maintenance. King County’s Department of Transportation compared the situation to the expensive automotive repairs that one would incur if they failed to change their motor oil periodically.

It’s no exaggeration to call this situation a “crisis.” The matter is time sensitive and the consequences of inaction will be severe. If the emerging 16-year transportation package restricts local jurisdictions from bonding for further road repair funds, there won’t be any mechanisms to fill these gaps. Preventive maintenance is a bargain compared to reactive maintenance. King County’s Department of Transportation compared the situation to the expensive automotive repairs that one would incur if they failed to change their motor oil periodically.

Brenda Bauer, chief of King County’s Roads Division, told KUOW: “We’re thinking things no one is thinking about nationally. Like how to sensibly close down a system and how to talk with people about that.”

The window to begin addressing this matter is now before the state transportation package cements a new status quo for transportation funding.