Two bills in the Washington State Legislature aim to incentivize and expand access to computer science programs in Washington’s K-12 schools. These bills have made it past the first cutoff in the legislative session.

SHB 1445, sponsored by Representatives Chris Reykdal (D-22nd) and Chad Magendanz (R- 5th), allows two years of computer science to be counted as a foreign language requirement in Washington high schools. Representatives Magendanz and Reykdal are also supporting HB 1813, which is primarily sponsored by Representative Drew Hansen (D- 23rd). That bill creates the “Computer Science and Education Grant Program” to address Washington’s shortage of computer science professionals. It requires OSPI to adopt standards supported by a nationally recognized computer science education organization.

What’s the Big Fuss?

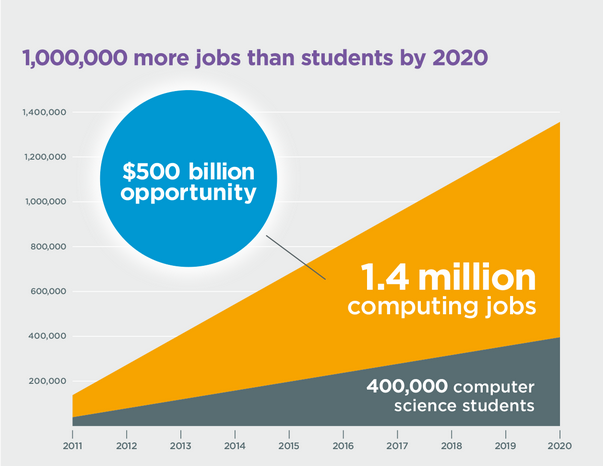

By not incorporating computer science into K-12 curriculum, the state is passing up opportunities at its fingertips. Not only is there a need for talent in the tech industry, but increasing participation in this industry benefits the overall economy.

A new study by the Washington Technology Industry Association claims that for each new tech worker hired, seven more jobs are created. Shortly after releasing the report, WTIA CEO Mark Schutzler spoke publicly about the need to invest in bringing computer science to K-12, saying, “Almost all the jobs that are being created in this economy require a degree in a STEM field…if you have to prioritize where you spend the money, the most logical place to invest is integrating computer science into the high school curriculum so that kids coming out of high school are prepared to enter that field.”

A report by the Washington Roundtable shows that approximately 80 percent of unfilled jobs are in “highly skilled STEM disciplines, such as computer science and engineering, and high-demand healthcare occupations.” The scarcity of computer science skills in particular is reflected in employers feedback as well. The Washington State Employment Security Department (ESD) reported that the top 25 most in-demand hard skills between 2004 and 2014 were highly concentrated in IT and software design. If that’s not convincing enough, Software Application Developer was the fastest growing occupation over the same time period, increasing by 227%.

Yet, despite the urgency displayed by industry leaders and the potential economic payoff, Washington’s educational system is failing to provide opportunities for students to learn the most in-demand skill set in our state.

Early Exposure is Key

Studies have repeatedly shown that early exposure STEM subjects is important in prompting students to think about careers in these fields. Earlier this year, Microsoft surveyed 500 college students pursuing STEM degrees, finding that nearly four out of five said they had made the decision to become STEM major in high school or earlier. Most notably, almost 70% of women (who are grossly underrepresented in the world of computer science) said this was what made them decide to study STEM (versus just 51% of boys).

Unfortunately, the availability of computer science courses prior to college in Washington state is dismal. The most reliable figures about computer science’s reach into high schools come from the Advanced Placement (AP) exam. Even though Washington is a renowned hub for programming, the AP Computer Science test is scarcely offered. Only 7% of public high schools in Washington offer an Advanced Placement (AP) computer science course.

Furthermore, AP Computer Science was only recently allowed to count for credit towards graduation in Washington high schools. It wasn’t until 2013 (with the passage of RCW 1472), that AP computer science courses could be counted towards math or science credit requirements.

K-12 Remains Absent from the Discussion

There is a strong effort to increase funding for computer science degrees in Washington’s public universities.

In 2013, the legislature appropriated $18 million to meet the soaring demand for engineering and computer science programs at the state’s public universities. The number of incoming freshmen intending to major in computer science at the University of Washington increased more than 50 percent over a period of 3 years. Similarly, Western Washington University has seen the number of its computer science majors and pre-majors double in two years. And, at Eastern Washington University, computer science and engineering have become so popular that the universities are literally running out of room to accommodate students.

Computer science in K-12 is a different animal. Whereas higher education simply needs more funding to expand existing programs, K-12 has no existing curriculum or standards for computer science, meaning that fewer resources, if any, are directed towards the subject. Additionally, K-12 education is governed by a complicated web of local, state, and federal authorities, making it difficult to institute change of any kind.

Who is Taking the Lead on Computer Science in K-12?

Across the country, state legislatures have given minimal attention to K-12 computer science, reinforcing the idea that workforce development doesn’t start until college. A report issued last year by the Association of Computing Machinery found that very few states offer K-12 computer science education at all. And, not a single state requires computer science for graduation.

The private sector has picked up the slack. Businesses and non-profits have become the main proponents of bringing computer science to K-12 students. While groups like the Association for Computer Machinery and Computing in the Core have pushed for computer science legislation, Code.org’s aggressive marketing campaigns, beginning in 2013, have generated public awareness.

Groups like Code.org, and Microsoft’s TEALS (which are based in Washington) even offer their own courses to middle schoolers and high schoolers interested in coding. In Washington, Code.org launched a new program in Fall of 2014, establishing permanent computer science programs in 11 Washington school districts. TEALS manages hundreds of industry-leading software programmers who volunteer to educate youth and mentor teachers in computer science. Additionally, companies such as Google and Microsoft contributed over 20 million dollars to train 25,000 teachers across the nation in time for the 2016 school year.

What’s the Hold Up?

While this year’s proposed legislation represents a step forward, we are a long way off from seeing computer science take root in Washington schools. Below is a list of the largest obstacles standing in the way of integrating computer science into K-12 learning.

- State Standards- The only state standards related to computers fall under the umbrella of “technology literacy,” which does not include computer science concepts and seems to be increasingly irrelevant as more and more children enter school with computer knowledge that extends far beyond that of the adults around them.

- Teacher Training- State certification programs for computer science teachers are either non-existent or incoherent. The necessity of teacher training is undeniable, because the likelihood of luring software developers into teaching positions.

- Graduation Requirements- Even when computer science courses are available in schools, they are rarely considered requirements for graduating. This impacts funding decisions, which are guided by graduation requirements and enrollment.

- Measuring Success- Assessments for computer science education are virtually non-existent. The recent wave of concern over tying education funding to measurable outcomes means that funding is increasingly contingent on baseline assessments to measure student performance, putting these courses at a significant disadvantage.

A National Movement

The need for computer science talent may be acute in Washington, but this is a problem of national scope. The Bureau of Labor Statistics projects that there will be 9.2 million jobs in STEM fields in the United States by 2020. Half of those jobs—4.6 million—will be in computing or information technology. This sector, in comparison to other fast-growing sectors, boasts the highest average salary–$78,730.

Thankfully, the idea of integrating computer science into core curriculum is gaining traction. Aside from Washington, 17 states and the District of Columbia now have policies in place that allow computer science to count towards mathematics or science credit in high schools. As of December 2014, Wisconsin, Alabama, and Maryland have adopted similar policies. And, nine more states are looking into adopting these types of measures.

Some of the greatest progress has taken place at the city level. The Chicago school district (the largest in the nation) implemented computer science into its core curriculum in fall of 2014, and it plans to make computer science a graduation requirement within the next few years. 60 other school districts have made commitments to offer computer science in middle school or high school, but have yet to take action.

Click here to view an interactive map of K-12 computer science offerings across the country.

Learning by Example

Across the globe, governments are recognizing the ubiquity of tech and the economic opportunities attached. These governments, sometimes in partnership with private companies, have moved quickly to get computer science into primary schools.

The leading example is Israel, which has had a computer science curriculum for high school students for 20 years. Often referred to as the “Start-Up Nation” (the country has the highest density of tech startups and attracts more venture capital dollars per capita than any other country in the world), the education system matches the drivers of economic growth. According to an article published in TIME magazine, “The number of high school students who take computer science is roughly the same as the number who take physics.” The standards for computer science teachers are high, too. At a minimum, teachers must have obtained a bachelor’s degree in computer science along with official certification.

In the past few years, other countries have followed Israel’s lead, exposing children to computer science as early as kindergarten. The United Kingdom’s decision to reconfigure K-12 curriculum, allowing children as young as 5 years old learn basic computer programs and algorithms. The curriculum became a requirement in fall 2014. In Estonia, a coding curriculum was introduced in 2013. The pilot project, known as ProgeTiiger, starts teaching basic coding skills to children as young as seven years old.

The effectiveness of exposing young children to computer science topics was demonstrated by a story that caught the media’s attention in 2013. Neil Fraser, an engineer from Google, visited a schools in Vietnam, a country known for introducing computer science into the curriculum at a very early age. Fraser remarked that students were able to solve Google interview-level coding puzzles before graduating high school.

Washington Should Take the Lead

Washington, more than any other state, has an incentive to be at the forefront of the movement to bring computer science to K-12 classrooms. The degree to which tech drives our economy continues to increase, especially as Washington cements its status as the hub for cloud computing.

An article from KQED perfectly summarizes the no-brainer logic behind adding computer science to K-12: “There are plenty of opportunities for students to take biology before stepping into a Biology 101 class in college; there are very few opportunities for students to take programming before stepping into CS 101.” At the very least, Washington students deserve the opportunity to learn foundational computer science knowledge, as they do in other subjects.

It’s not just about closing the skills gap. Computer science skills are increasingly important across all fields. Like reading, writing and arithmetic, they are on a path to becoming part of a foundational skill set that pertains to all career fields.