In Washington State, it’s not safe to eat seafood everyday. The good news is that Washington’s Department of Ecology is hoping to change that. The bad news — it’s easier said than done.

On September 30, the DOE introduced a preliminary draft to update water quality standards in the Evergreen state.

“There are all sorts of standards concerning the quality of our water,” said Sandy Howard, the Department of Ecology’s spokesperson for water quality. “Right now, we are working on updating the human health criteria, which basically says the water needs to be clean enough for us to eat the fish that swim in the water.”

However, without due consideration, changing regulations could be devastating to the local economy. So, the draft is under scrutiny.

THE LAW

All states are bound by the Federal Clean Water Act, which requires states to enact and uphold water quality standards. The standards determine how clean the waters need to be and guide states in setting regulations to uphold those standards.

A key component in the equation is fish consumption. How much fish Washington residents eat helps determine the necessary water quality. The rule is called the Fish Consumption Rule, and it assumes that if people are eating less fish, more pollution can be tolerated. As fish consumption increases, so too must the quality of the water.

But why make changes now?

The Federal Clean Water Act requires that states keep their standards up-to-date with contemporary science. That’s where Washington State falls short, Howard said. Washington’s Fish Consumption Rule is set at an outdated 1992 federal minimum, allowing for residents to safely consume only 6.5 grams of seafood per day. That’s slightly more than one serving of fish per month.

New studies conducted by the DOE and local Indian tribes show this number is too low. Some high level consumers, such as certain Indian tribes, eat as much as 225 grams (about 8 ounces) of seafood per person daily. After some research, the DOE chose 175 grams of fish per day as the new standard.

“We wanted to propose a reasonable range that was both manageable for businesses and healthy for the environment,” said Kelly Susewind, special assistant at the DOE’s ecology headquarters. “The 175 gram number is in the middle range of that range.”

An increased FCR needs to be accompanied by new regulations to clean up the water. That’s where wastewater comes into the picture.

WASTE IN THE WATER

Wastewater is the largest contributor to water quality degradation. Consequently, any attempt to improve water quality will have impacts on how wastewater is treated.

So, what is wastewater?

Under natural conditions, before the land is developed, there is little surface runoff from the land. Water falls from the sky and is absorbed into forests and soil before it is released back into streams. This is the environment in which aquatic life thrives. However, land development complicates the process.

With developed land comes commercial and residential development, and with development comes waste. That waste from air and water affluent finds its way into the runoff. When it rains, water washes over the earth and collects a variety of toxins. That polluted water, called stormwater or wastewater, runs off into streams, lakes and other water sources, polluting aquatic habitats and poisoning the life within.

An important factor in water quality is how municipalities regulate this wastewater. That means regulating the elements that end up in the water.

The DOE’s preliminary draft proposes an update to the acceptable levels of polluting chemicals in Washington waters. This would work hand-in-hand with a toxics-reduction package that Governor Inslee plans to introduce during the 2015 legislative session. That package would, among other things, ban the use of especially harmful chemicals that have safer alternatives.

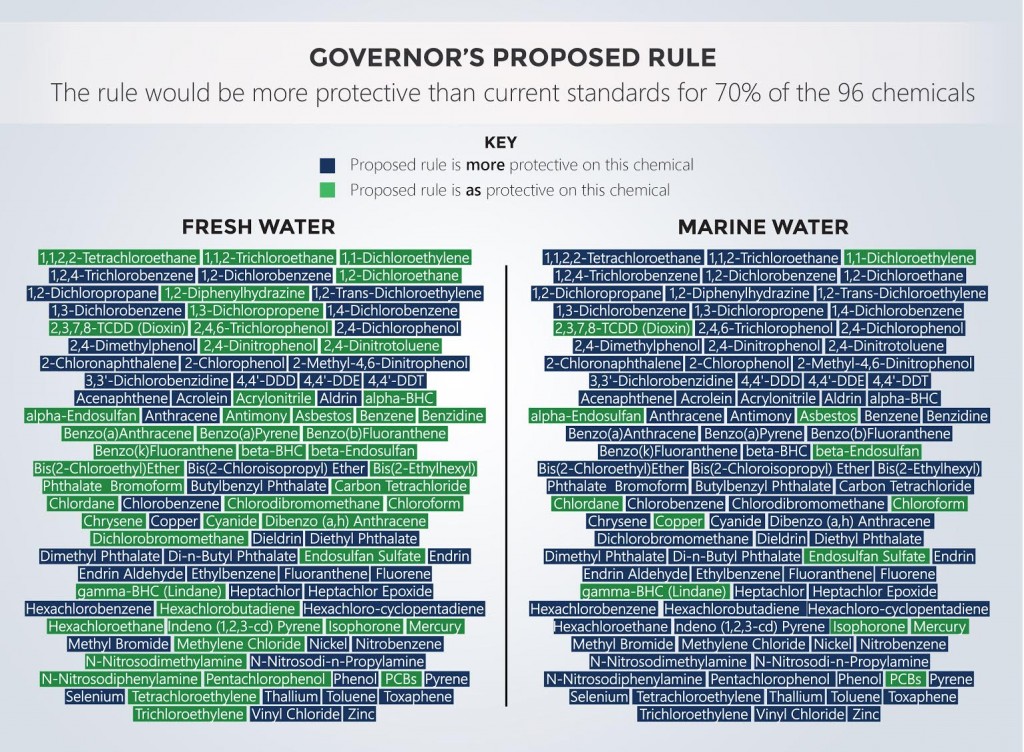

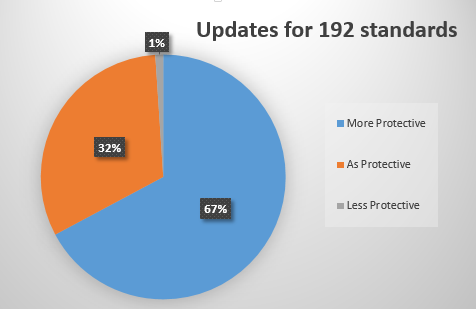

Of the 96 chemicals with regulatory standards, more than half would receive more restrictive standards. Most remaining chemicals will be kept at the same standard.

THE CONFLICT

Stricter regulations will place a burden on Washington businesses and homeowners. That’s why some businesses and business representatives are concerned.

Representatives of the Boeing Company, such as Environmental Communications Representative Joanna Pickup, have voiced opposition to FCR increases. Pickup said the company is concerned that the governor’s new standards would result in little or no improvement to water quality and would be a substantial detriment to Washington’s economy.

Representatives of the Boeing Company, such as Environmental Communications Representative Joanna Pickup, have voiced opposition to FCR increases. Pickup said the company is concerned that the governor’s new standards would result in little or no improvement to water quality and would be a substantial detriment to Washington’s economy.

The biggest concern from the business community is that it will be too difficult comply with the proposed changes. For example, standards for some chemicals would be set below levels that are currently detectable. The DOE says that, because current methods can’t measure such small chemical concentrations, there would be no impact on businesses that discharge those chemicals. However some organizations fear that, in 20 to 30 years, the timeframe in which businesses plan, methods and technology will change, driving up the cost of compliance.

As detection methods change and it becomes more difficult to comply with toxic standards, businesses would need to invest in new technologies and infrastructure to keep up-to-date. Some complain that the DOE is not accurately calculating the long-term impact of potential changes on businesses.

In a nutshell, ideal regulation would help protect Washington’s economic environment as well as its water. If it becomes too costly to keep in compliance with changing regulations, businesses may be less inclined to set up shop in the Evergreen state. That means fewer jobs and less economic development. That’s what lobbyists are trying to prevent.

The complaints don’t stop there. In addition to economic concerns, there remains reluctance from Indian tribes, some of which feel that the measure doesn’t go far enough to improve public safety.